Corpus annotation

Corpora typically contain within them three types of information that can help in investigating the data: metadata, textual markup, and linguistic annotation.

Metadata and markup

Metadata is information that tells you something about the text itself – for example, the metadata may tell you who wrote a text and when it was published. The metadata can be encoded in the corpus text, or held in a separate document or database.

Textual markup encodes information within the text other than the actual words, for example, the sentence breaks or paragraph breaks in a written text.

In spoken corpora, the information conveyed by the metadata and textual markup may be very important to the analysis. The metadata would typically identify the speakers in the text and give some useful background information on each of them, such as their age and sex. Textual markup would then be used to indicate utterance boundaries.

For example, in the BNC, each utterance is marked up and is linked to the metadata for a particular speaker. For each speaker, the following metadata is stored:

- Name (anonymised)

- Sex

- Age

- Social class

- Education

- First language

- Dialect/Accent

- Occupation

We can use this metadata to limit searches in the BNC in a linguistically motivated way — for example, to extract all examples of the word surely as spoken by females aged between 35 and 44.

A system of encoding called XML (the eXtensible Markup Language) is often used for both markup and metadata. It is based on angle-bracket tags such as <u> and </u> for the beginning and end of an utterance, respectively.

Linguistic annotation

We can also encode linguistic information within a corpus text, so that we can describe it as analytically or linguistically annotated (see our discussion in part 1). Annotation typically uses the same encoding conventions as textual markup. For instance, the angle-bracket tags of XML can easily be used to indicate where a noun phrase begins and ends, with a tag for the start (<np>) and the end (</np>) of a noun phrase:

<np>The cat</np> sat on <np>the mat</np> .

A wide range of annotations have been applied automatically to English text, by analysis software (also called taggers) such as:

- constituency parsers such as Fidditch (Hindle 1983)

- dependency parsers such as the Constraint Grammar system (Karlsson et al. 1995)

- part-of-speech taggers such as CLAWS (Garside et al. 1987)

- semantic taggers such as USAS (Rayson et al. 2004)

- lemmatisers or morphological stemmers

(We discussed how you can get access to some tagger and parser tools in Part One.)

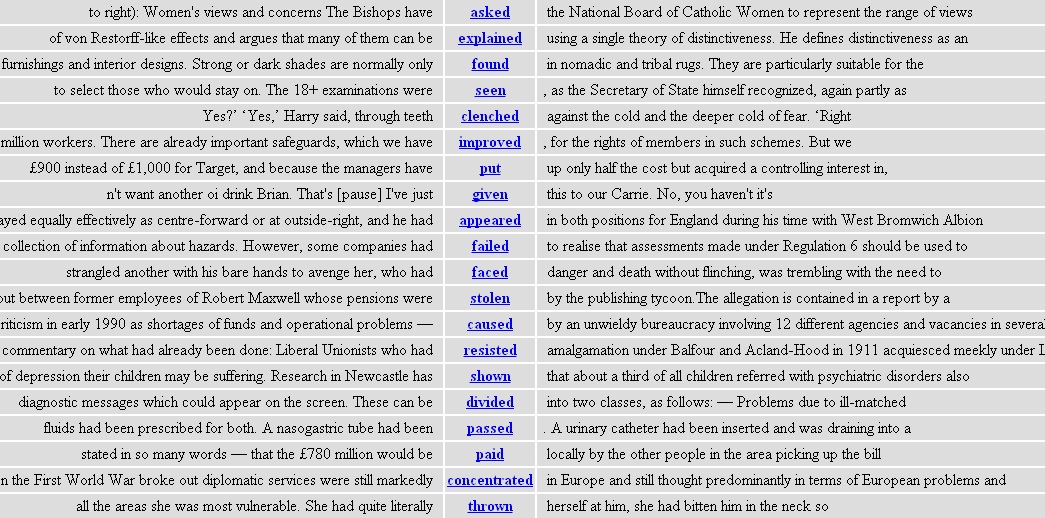

The virtue of all these forms of annotation is that, when they exist in a corpus, we can run searches for the tags rather than word-forms. For example, here are some of the results from a grammatically-aware search for all words tagged as a past participle in the BNC (preceding link requires a BNCweb log-on):

As you can see, searching for a tag (in this case, the part-of-speech tag VVN) allows us to capture a group of related words without specifying each one individually. Here the words are related grammatically (all past participles) but the same principle is at work with semantic relations if we search for words with a particular semantic tag. With a syntactically-parsed corpora, we can search for particular grammatical structures without regard to the actual words that represent those structures.

Next, we'll look in more detail at corpus search tools and what we can do with them. Click here to continue.

This page was last modified on Sunday 30 October 2011 at 10:04 pm.